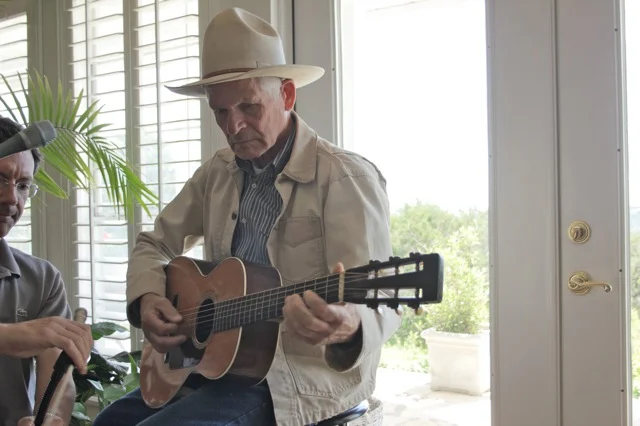

Tamara Kubacki interviewed Skip Gorman about the appeal of cowboy music, playing with other musicians, and the importance of teaching and learning about history.

LISTEN to Buffalo Hump

[audio http://westernfolklifecenter.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/buffalo-hump-by-skip-gorman-sg-edit.mp3]

TK: You listened to and watched musicians from an early age, and you received your first guitar when you were eight. When did you become interested in cowboy music?

SG: I think I first became interested in cowboy songs when I was around 10 or 11 years old and heard recordings of Jimmie Rodgers. He wrote and sang a few very authentic-sounding western songs. Then Bill Monroe covered Rodgers’ “When The Cactus Is In Bloom,” and of course, Bill used to sing Cliff Carlisle’s “Goodbye Old Pal” a lot when I started listening and playing bluegrass music. Later when I was in grad school in Salt Lake City and in the Deseret String Band, Hal Cannon and I used to find and listen to old 78 records of some of the cowboy greats like Carl T. Sprague, Powder River Jack Lee and Jules Verne Allen. Also around that time in the 70’s Glenn Ohrlin was re-discovered by the old-time music crowd at folk festivals. So this all piqued my interest in the history of the music of the West.

TK: Your music brings not only a glimpse into the history of the cowboy, but also a truth about life on the ranch or the range. You worked as a cowboy in Wyoming for awhile, too. What is the appeal of the cowboy to you and to fans of the music?

SG: Though I lived in Utah for 6 years, I was not raised in the West. So I never started riding and working on ranches until I was in my 40’s. Then I was hired on at a dude ranch to entertain at recreations of 1880’s cattle drives. It was then that I got a good taste of what I had been singing about for 20 years. It was a fascinating way to go!

What appeals to me most about the cowboy is similar to what appeals to me about old time New England Farmers: they have an astute sense of independence . . . the dogged determination to get things done right, even under lonely, very difficult circumstances.

TK: The songs and tunes you play were influenced by many different traditions: Celtic, Appalachian, Spanish and African-American music. It’s quite a diverse tradition. How do you wade through the long history to find the songs that speak to you?

SG: Because I’m so partial to old-time sounding, unplugged music, I’m always charmed by melodies that speak with a historic flavor, whether they are Celtic based or south of the border in feel. And then the lyrics that tell the story are the icing on the cake for me. Ironically, this appears to be the opposite of how many of the old time cowboys put together their "songs." For them the story was the primary focus. Therefore, lyrics came first and the melody was often attached to the story line later. Their stories and poems were of prime importance.... not music or any hot picking or licks. I like being transported back to a time before Hollywood and jazz, swing and blues seemed to permeate and take over most everyone’s musical sensibilities.

TK: Along with playing music, you also teach workshops and school programs on playing music, cowboy songs, and the history of the West. You will be teaching a fiddle workshop and giving a talk about the history of cowboy music at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. Explain the importance of teaching.

SG: Yikes! One can cover acres answering this question. I think teaching is merely introducing to someone—in an exciting way—something that they may not be familiar with at all, or being able to convince a person to view something from a very different angle.

When I go into schools to teach kids about the West, they are often surprised to learn that there’s a lot more to it than cowboys in fist fights, gun battles with Native Americans and yodeling.

When they hear the flavor of the older music and actually see a map of an emigrant or cattle trail, they are often pleasantly surprised and fascinated.

TK: You play solo, as a duo with Connie Dover, and with a group, The Waddie Pals. Connie and the Waddie Pals will be joining you at the Gathering. Will you talk about what it’s like to play music solo, with Connie, and with the Waddie Pals? What makes a good partnership?

SG: Playing gigs as a solo act certainly allows you the freedom and spontaneity for a concert or program to develop freely as you size up and play the audience. Yet, doing this alone is often much more work, lonely travel, and usually not as exciting. Singing with Connie Dover gives me a stellar voice to try to match. It takes me to another level and I enjoy being with her immensely. Like Connie, the Waddies are old friends. What’s more fun than spending time with old musical pals?

LISTEN to Powder River, Let 'er Buck

[audio http://westernfolklifecenter.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/powder-river-by-skip-gorman.mp3]

TK: You have a new recording in the works, Fiddles in the Cowcamp. Tell us a little more about it, please.

SG: When I saw how people were enjoying Mandolin in the Cow Camp, which I recorded a few years ago, I realized that there was a need for a similar project with the fiddle. Yet, doing all the mandolin playing on close to 80 tunes on a double set had been a load of fun for me but a huge amount of work.

I immediately thought of some of my fellow fiddler pards in the West whose music very much deserves to be heard more. People like Ron Kane, Tom Carter and Ruthie Dornfeld have something special when it comes to rendering an old fiddle tune with time-honored nuance and a true sense of what the music most probably sounded like before Hollywood. Their music is the style of fiddle playing that would have been done in cow camps before the 1930s or so. They use older bowing styles, cross-tunings, clawhammer banjo accompaniment and rhythm as was done in the West as far back as the 1800s. We’re excited about this project and it’s with great old pards.

TK: Thank you for taking the time to answer my questions.

SG: Thank you Tamara! We’re looking forward very much to being at the Gathering this year.

The Western Folklife Center received a TourWest grant from WESTAF to help cover some of the travel costs for Skip Gorman, Connie Dover and the Waddie Pals. Skip and Connie will perform on Tuesday, January 30 and Saturday, February 4, 2012, and the Waddie Pals will join Skip during some of the daytime performances, February 2 - 4. Skip is also conducting a two-day fiddle workshop on Tuesday, January 30 and Wednesday, January 31. Please join us at the Gathering.

![4599341765_3f4b218b7c_m[2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56972f85b20943f1333a2f06/1469421726508-L6R1UA8E1SA286IKFPDK/4599341765_3f4b218b7c_m2.jpg)