By Piper Wiest

When I first told my grandma, a spry and active 75-year-old rancher in Central Texas, that I was starting a remote internship at the Western Folklife Center last summer, she quickly rustled up a collection of cowboy poetry. The book was yellowed with age but, undeniably, had a cowboy on the cover. As I flipped through the pages, I didn’t recognize names or titles. When one poem in particular stuck out to me, I held the book open to my grandma and she started to read the poem aloud in perfect rhyme and rhythm.

That was my first official introduction to cowboy poetry. I say official because I realize now, after reading and listening to many more cowboy poets last summer, that I’ve encountered aspects of the genre before. I grew up listening to my grandma tell stories about the weekly ranch happenings: a snake in the chicken coop, a cow on the front porch, a goat on the barn roof. No matter the story, my grandma often spoke colorfully and with character. Although my grandma has never attended the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering or any poetry gathering closer to home, she espouses its artful storytelling component. And as I’ve now learned acutely, cowboy poetry covers many topics and takes many forms.

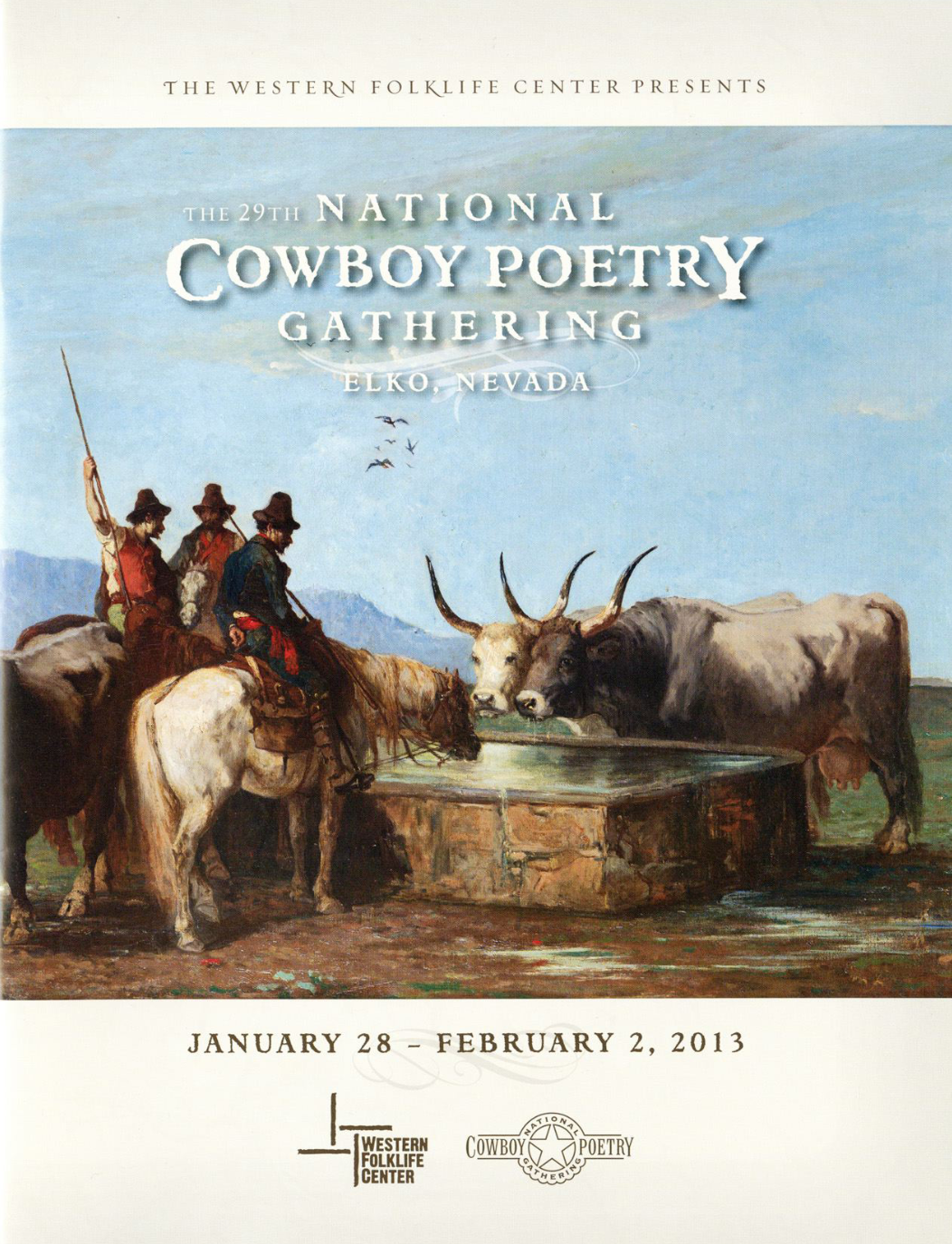

I realized that tenet of cowboy poetry especially through the work I did last summer. As an intern, I typed up log sheets from past National Cowboy Poetry Gatherings. I started with the year 2009 and ended with 2013. From those five years, I got a good sense of the range of topics and artists the Gathering hosts each year. While I began to recognize some of the same poets and poems, I also saw many new, unique artists.

The Gathering in 2010 hosted a few events focusing on cattle ranching in the Southeastern United States. One event in particular put what was running through my head bluntly: There are Cowboys in Florida? Similarly, the National Cowboy Poetry Gatherings in 2011 and 2013 hosted csikosok (herdsmen from Hungary) and butteri (cowboys from the Italian Maremma). For me, seeing those different perspectives elevated the national event to a global one and emphasized the community building the Gatherings generate.

In addition to a range of artists, the five Gatherings I looked at also focused on and responded to a range of current events. One that stood out to me especially was an event from the 2012 Gathering called Texas Drought. From what I saw from the log sheets, several well-known cowboy poets recounted the 2010-2012 Texas drought through poetry, song, and stories.

The tank drying up at my grandma’s ranch this summer, 2023.

Although I was young, I do remember that drought. Mainly, I remember how it killed off most of my grandma’s orchard. But what stood out to me about that gathering event most of all was the fact that last summer, 2022, and this summer, 2023, many parts of Texas were drought-ridden once again. For me, hearing poems, songs, and stories of a shared experience like drought provides a bit of relief. It’s a recognition which leads to reconciliation, in a way.

While most of what I did as an intern was type titles and artists as they were written on log sheets into a spreadsheet, I was able to watch artists perform their poems and songs through the Western Folklife TV streaming service. Seeing the artists and hearing their voices added a whole new and colorful dimension to this work. Additionally, I was able to watch and listen to more recent gatherings, as well as the initial 1985 Gathering, which allowed me to place the years I looked at closely in context of the wider history of the Gathering.

I’m curious now to go back and look at that initial collection of cowboy poetry my grandma showed me. I’m certain I’ll recognize some names and titles. And this January, I’m looking forward to attending the 39th National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in person.

Piper Wiest was born and raised in Austin, Texas. She comes from four generations of Central Texas ranchers and often spends time out on the family ranch. In summer 2022, she interned for the Western Folklife Center. Piper recently graduated from Smith College as a history major and currently works part-time for the Western Folklife Center as a communications assistant.